Furniture has always been more than background. Even in the earliest video games—crude, blocky, barely resembling reality—developers used furniture to create a sense of place. A square brown blob in the corner wasn’t just visual filler; it was a table, a couch, a dresser. It told the player: This is a room. That mattered.

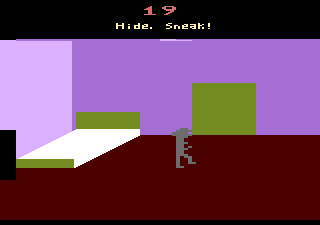

Early consoles like the Atari 2600 and arcade cabinets had limited visual range. Developers relied on color blocks and fixed sprites to build environments. Yet even within these constraints, furniture was present—if only as a suggestion. A digital home still needed a couch.

The 1970s aesthetic was particularly distinct. Homes were earth-toned, tactile, and layered with texture. You’d find burnt orange pillows, shag carpets, avocado green appliances, and teak wood everything. Modular seating and sunken living rooms mirrored society’s desire for togetherness and modernity. Design embraced both comfort and boldness.

Games didn’t fully capture these details, but the feel made its way through. Players recognized spaces based on real-world familiarity. A CRT television in the corner, a coffee table centered in front of a chair—it told a story, however pixelated. As game graphics evolved, so too did the furniture. And what began as a vague blob became an object with presence.

The 70s Living Room, Game-Style

Step into a 70s digital home and you’re met with a very specific visual grammar. Whether it’s a modern game leaning into nostalgia or a classic title from the era, the design signals are immediate.

Burnt orange, avocado green, mustard yellow—these tones dominate retro-themed environments. Walls are wood-paneled. Floors wear thick rugs. Light leaks in soft and golden, bouncing off chrome lamp stands and plush couches. Games that invoke this aesthetic—Unpacking, Lake, The Sims 4: Throwback Fit Kit, or Control—use color and furniture to situate the player firmly in a time period.

The forms of 70s furniture stand out. Curves ruled the room. Egg chairs, bean bags, sunken seating pits. Tables were low and often oval. Coffee tables came with brass accents or smoked glass tops. In games, these shapes tend to exaggerate their real-world counterparts, sometimes for stylistic clarity, sometimes to enhance nostalgia. Pixel art indie titles, in particular, lean on these instantly recognizable silhouettes.

Functionality? Almost nonexistent. In older or retro-styled games, furniture was static. You couldn’t sit on the couch. The lamp wouldn’t switch on. It was scenery, not gameplay. But its purpose was never just visual. It added mood—something soft, analog, and calm. A signal that you were in someone’s home, not just a room.

Control’s aesthetic, for instance, combines brutalist architecture with elements of 70s décor. Despite the surreal setting, you find familiar couches and filing cabinets that root the environment in a particular sensibility. The 70s weren’t just decoration—they were narrative texture.

In these spaces, furniture doesn’t move, but it moves you. It frames memory. It calls back to the domestic life of another time, evoking the warmth of physical presence in a digital world. The stillness is part of the charm.

Fast-Forward: Today’s Digital Decor

Today’s in-game furniture looks, feels, and functions differently. The visual fidelity is higher. Surfaces reflect light accurately. Materials mimic their real-world counterparts. But the biggest shift? Furniture is no longer just decoration—it’s part of the narrative and often part of the gameplay.

Modern design in games mirrors contemporary interior trends: clean lines, open spaces, cool neutrals, and light wood. Think Scandinavian simplicity with an urban twist. You’ll find Eames-inspired chairs, mid-century cabinets, and modular sofas in shades of grey, cream, and beige. The Sims 4, Paralives, House Flipper, and Design Home let players design spaces in extreme detail, right down to the material texture and placement of cushions.

Furniture now serves both visual and interactive functions. You can sit on it, move it, even dismantle and reassemble it. In House Flipper, furniture becomes part of the player’s job. In Paralives, each object has adjustable dimensions and colors. In The Sims 4, furniture not only reflects style but impacts gameplay (a better bed means better sleep).

Some AAA games integrate furniture into the emotional landscape. In The Last of Us Part II, abandoned homes are furnished with realistic layouts—dining tables half-set, couches sunken in from use, bookshelves full of believable clutter. These scenes tell quiet stories of lives interrupted.

Cyberpunk 2077 takes a more dystopian but equally detailed approach. Neon accents, chrome surfaces, smart furniture. The environments signal class divisions and societal collapse. Your apartment’s design reflects your narrative role. Furniture here isn’t nostalgic—it’s commentary.

Brands are also making appearances. Real-life items show up in virtual spaces. IKEA-inspired packs appear in simulation games. Luxury brands experiment with digital showrooms. This crossover reinforces the realism—and shows how digital furniture is no longer a stand-in. It is the product.

Customization has become the norm. Players expect to design their digital spaces. Whether decorating a personal apartment in an RPG or flipping homes in a simulator, the aesthetic is part of the identity. And that identity is sleek, conscious, and curated.

Today’s games use furniture as an extension of self-expression. Want a rustic farmhouse table next to a cyberpunk neon sign? Go ahead. Want a minimalist loft with nothing but a bean bag and smart light panel? It’s yours. The rules of design still exist, but the player writes them.

Materials, Mood, and Meaning

Furniture is tactile—even when it’s virtual. A velvet couch communicates something different from a steel bench. In games, material choices are deliberate. They shape mood and meaning. They also help signal setting and story.

The 70s leaned into rich, warm textures. Corduroy, velour, shag. Tables were solid wood or wood veneer. Legs were thick. Chrome and glass appeared as futuristic accents. Furniture had presence—often oversized, heavy, and geometric.

Modern interiors, both real and virtual, favor light. Literally and metaphorically. You’ll find pale wood, recycled composites, molded plastic, and engineered materials. Surfaces are matte or softly reflective. Pieces feel lighter, cleaner, and often modular.

In games, this translates into furniture that looks breathable. Sustainable design trends seep into digital spaces. Eco Lifestyle (an expansion for The Sims 4) features recycled wood counters, reclaimed metal frames, and solar furniture. Players learn the language of materials without realizing it.

Texture helps with worldbuilding. A dusty leather armchair signals abandonment. A polished marble kitchen counter suggests affluence. Shag carpet implies retro. In this way, furniture becomes narrative shorthand.

One small but telling example: “Even in titles set in restaurants or cafes, touches like authentic restaurant furniture help anchor the player in time and place.” It’s not just a chair—it’s the right chair. Context matters.

As games move toward realism or stylized authenticity, material becomes a storytelling tool. The way light hits a grainy table tells you more than dialogue might.

Interaction and Identity

In the 70s, modular design reflected a cultural shift. People wanted rooms to adapt to their lives—not the other way around. That logic persists in games today, especially those that center around home-building and self-expression.

Customization has gone from novelty to expectation. Players want to rotate, recolor, resize, and remix their digital spaces. And they want furniture to do something—not just sit there.

Games like Animal Crossing, My Time at Portia, and Dreams go further: furniture placement affects gameplay, mood, or productivity. In Stardew Valley, what you place in your home can impact your relationships. In The Sims, furnishing choices affect your Sim’s wellbeing and social status.

Furniture becomes an identity marker. A high-end minimalist couch signals restraint and taste. A cluttered boho corner implies creativity. A room with nothing but essentials may represent survival.

This mirrors real-life lifestyle shifts: digital nomadism, tiny homes, urban nesting. Players build what they can’t in real life—or replicate what they have with pride. The line blurs between aspiration and simulation.

The retro revival has come full circle. Players seek out mid-century credenzas, vinyl players, and shag rugs in-game. Nostalgia meets modernity. The furniture of the past becomes a tool for self-definition now.

Design in games is no longer about realism. It’s about resonance. Whether it’s creating a cozy space that feels like home or building a surreal dream room, furniture bridges the digital self and the real one.

Why the Difference Matters

Games mirror us—our tastes, values, and how we live. Furniture, though often overlooked, is central to that reflection. The shift from static, pixelated couches in the 70s to smart, interactive, customizable interiors today says something about more than graphics.

It reveals how we see space. In the 70s, furniture was a cultural artifact—tied to status, trends, and shifting domestic roles. In games, it appeared as part of that visual vocabulary, even if simplified.

Today, furniture in games is personal, editable, and layered. It tells stories. It invites interaction. It reflects the modern emphasis on identity and lifestyle. Comfort and style coexist with purpose and context.

Games that remix the two eras—bringing retro furniture into hypermodern engines—capture the tension between nostalgia and innovation. They allow players to hold both ideas at once: a love for analog warmth, and a desire for digital freedom.

Design isn’t passive anymore. It’s part of the game. And furniture, from pixels to pine, is part of how players shape their world—one chair, table, or shelf at a time.

Your total news and information resource for all things Science, Technology, Engineering / Mathematics, Art, and Medicine / Health.

Your total news and information resource for all things Science, Technology, Engineering / Mathematics, Art, and Medicine / Health.

Leave a Comment